Decorating With The Dead

Skin, Bones and Shells as Symbols

Honoring the dead with beauty, art and spirit

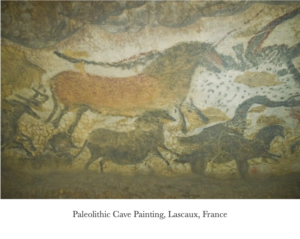

Nature always wears the color of its spirits, said Ralph Waldo Emerson. And people have always decorated from nature. Caves in Lascaux, in the south of France, are decorated with depictions of horses by early hominids. Later, Egyptians painted Papyrus, sacred cats and other objects from nature on their tomb walls. American Indians actually painted their horses before battle, turning organic objects into artistic symbols of strength and power. Of course, Europeans have celebrated flowers, animals and the human form in glorious oil paintings starting in the Renaissance and up to our present time. Over the course of religions, organic symbols have played a major part in art, some being, perhaps, more morbid than others. One often sees lilies as symbols of death in Renaissance Christian works, not to mention dying fruit, skeletons and skulls as reminders of our mortality.

To see some our past projects, follow the link below

>>Portfolio<<

After a recent visit to Prague, my dear friend, Ulli, kindly drove me out of the way to a little chapel I’ve wanted to see for years: Sedlec-Kutná Hora. In the 13th century a magnificent monetary was built in the town of Sedlec, on the present-day outskirts of Kutná Hora. One of the obligations of the Parrish there was to bury the dead. After a pilgrimage to the Holy Land an abbot brought back a handful of dirt from the grave of the Lord and spread it in the cemetery, making it a holy place. People clamored to be buried on the holy ground, and the cemetery held the dead from near and far. During the Plague of 1318 about 30,000 souls were added to the cemetery and, later, many more thousands were buried from the gruesome Turkish invasions. In 1421 the (Turkish) Hussites burned down the monastery, and many battles took place in the area.

The number of large churches built in and around the town of Sedlec is amazing. One chapel, in particular, is the one I wanted to see: the Cemetery Chapel, with the Ossuary on the first floor. Bones from abolished graves, skeletons from the Plague and war victims neared about 70,000. Many were piled up in mounds within the Ossuary and gathered around the perimeter. A half-blind monk made these into neat pyramids in 1511.

In 1661 the, by then, dilapidated chapel was rebuilt, and haphazard bones were organized into more decorative forms. In the early 18th century Jan Sandinista Aichl reconstructed the chapel, and in 1784 a wood carver named Frantisêk Rint enhanced the interior by making lavish decorations from the bones. He kept two of the skull pyramids, and added fantastic, wood obelisk candelabra featuring skulls, scapulae, tail and arm bones with baroque, carved and gilded putti at the tops, and a huge, magnificent chandelier made of thousands of bones. As a seashell artist, I was fascinated to see the creativity of these fabulous objects, reminding me of the limits of life, but the limitless fruits of death, as it were. To me, these magnificent objects show the utmost respect for the dead. Isn’t it better to create beauty from these nameless crowds of bones, rather than leaving them in piles on the perimeter?

Seashells are also skeletons, and I try to show respect for death in the sea by creating objects of beauty and, hopefully, some meaning from Murex, Clams and the huge variety of shells in my collection. Many of the seashells are symbols in and of themselves, such as the Cowrie, which is an age-old symbol of fertility in Tibetan and Indian culture. The Nautilus symbolizes eternity, with its ever-widening chambers that grow until it reaches a crescendo. The Scallop is the signature and symbol of St. James, who carried one on his pilgrimages. To this day the Scallop is used to mark the many caminos (paths) to the church of Santiago in Spain, where St. James’ remains are said to be. Thousands each year make a pilgrimage along the Jacobsweg in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Paths can also be found in France and Czechoslovakia. The marker is the very Coquille St. Jacques epicureans have long enjoyed!

Where some may find decorating with bones, seashells and other organic “leftovers” morbid, I find an exquisite beauty and honor for those objects in their use. My love of shells grows eachtime I see other “pieces of nature” used in art and decoration. I believe making chandeliers, sculptures and even frames from natural byproducts elevates as well as recycles those things. The urge to decorate is one idea that separates humans from other animals. We’ve done it since the Stone Age and will continue to use objects as symbols until the end of time. This strange homage to nature and death is one of my favorite things that people do with their time.